The Coming Collapse of China?

Is it vogue to be pessimistic about China’s economy? Andy Rothman explores.

SubscribeKey Takeaways

- The consensus view of the Chinese economy may be too negative, underestimating the resilience of Chinese consumers and entrepreneurs, and the pragmatism of policymakers.

- As memories of COVID fade, consumers should regain more confidence, supported by high savings and strong income growth.

- The government is voicing enthusiastic support for the private sector, including platform companies, in an effort to restore entrepreneurs’ animal spirits. A gradual, consumer-led economic recovery is likely in the coming quarters.

- The Biden administration’s recalibration of its China policy won’t make the relationship much better in the near term, but should stabilize it, reducing the risk that an accident spirals into a crisis that neither side desires.

It’s in vogue to be pessimistic about China’s economy, but is the consensus view too negative?

Recent data signals that a gradual, consumer-led recovery is underway, and the two main, short-term obstacles to a return to pre-pandemic growth levels are likely to recede in the coming quarters. First, most of the developed world moved on from COVID two years ago, while the last wave of COVID cases and deaths in China only ended in January, restraining household sentiment and spending. With each passing month, Chinese consumers should regain more confidence, supported by high savings and strong income growth. Second, in July, the government took the pragmatic step of voicing enthusiastic support for the private sector, including platform companies, in an effort to restore entrepreneurs’ animal spirits, which have been weak for two years.

The resilience of Chinese consumers and entrepreneurs, as well as the pragmatism of the country’s policymakers, have often been underestimated, and that is likely the case again today.

In his 2001 book, The Coming Collapse of China, author Gordon G. Chang forecast that China’s “economy, and the government, will collapse. We are not far from that time.” Similarly dire predictions for China’s economy were common during the Global Financial Crisis, the Trump trade war, and the COVID lockdowns.

Instead, between 2001 and 2022, inflation-adjusted (real) per capita income rose 4.6 times in China, compared to 33% in the U.S. and 22% in the UK. The Chinese economy has been stressed, but has, over the last decade, accounted for about one-third of global growth, larger than the combined share from the U.S., Europe and Japan. All of that, of course, is ancient history for investors, who are asking, what is the Chinese economy doing for me today?

Before answering that question, I’d like to remind readers why I generally have a glass-half-full perspective on the Chinese economy.

A framework for thinking about China

One of the fundamental elements of my framework for thinking about China is that the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), including under Xi Jinping, has been successful when its economic policies have been pragmatic. They have made plenty of mistakes but have course-corrected to a more pragmatic path. The second element of my framework is that Chinese families and entrepreneurs are resilient.

When I first visited China as a student in 1980, its per capita GDP was less than that of Afghanistan and Bangladesh, and 80% of China’s population was living below the World Bank’s poverty line. The Cultural Revolution had left the education system in tatters, with very few university graduates. Few foreign investors had interest in China, and there was little reason to believe that would change.

Today, Chinese consumers are estimated to account for 20% of global luxury sales, and in 2021 the country installed more industrial robots than the rest of the world combined. Since the mid-2000s, China has consistently produced more science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) PhD graduates than the U.S., and a study by Georgetown University forecast that by 2025, Chinese STEM doctorates will be nearly double those in the U.S.

When I returned to China in 1984 as a junior American diplomat, there were no private companies—everyone worked for the state. Today, almost 90% of urban employment is in small, privately owned, entrepreneurial firms. Private companies are responsible for China’s job, innovation and wealth creation.

All of that progress was the result of pragmatic policies that emphasized market-based reforms and de-emphasized the economic role of the state. Those policies rarely followed a consistent trajectory, but Chinese people were resilient enough to overcome obstacles and find new opportunities.

The last several quarters have been rough, but Xi’s 10-year, economic track record as Party chief has been pretty good. Between 2012 and 2022, China recorded average annual real income growth of 6.2% (vs. 1.4% in the U.S. and 1% in the UK); average annual real retail sales growth of 6.7% (vs. 4.4% in the U.S. and 2.2% in the UK); and China accounted for 33% of global economic growth during that period (vs. an 11% contribution from the U.S. and 1% from the UK).

The growth of the private sector and the rebalancing of the economy continued during the last 10 years. The share of employment and of exports accounted for by privately owned companies rose, and last year was the 11th consecutive year in which the services (tertiary) part of GDP was larger than the manufacturing and construction (secondary) part.

Witnessing these changes has had a significant impact on my framework for thinking about the Chinese economy, and I’m aware that it leaves me with a glass-half-full perspective. I work hard to ensure that this bias does not lead me to miss negative developments.

Back to the future

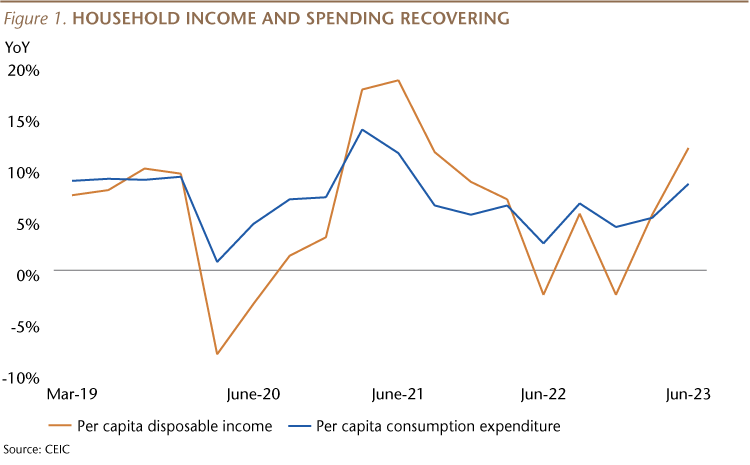

With that background in mind, let’s look at prospects for a post-COVID recovery. There are green shoots in the services sector, which is the largest part of the economy and the biggest employer. In the first half of 2023, per capita spending on services rose almost 13% year-over-year (YoY). Domestic tourism revenue during the first six months of the year, for example, increased 96% YoY. This was fueled by strong income growth: an increase of 8% YoY in real terms in the second quarter, up from 4% in the first quarter and the fastest pace since the third quarter of 2021. One of the brightest data points is that in each of the last two quarters, household consumption increased at a faster pace than the growth rate of income, signaling an initial recovery in consumer confidence.

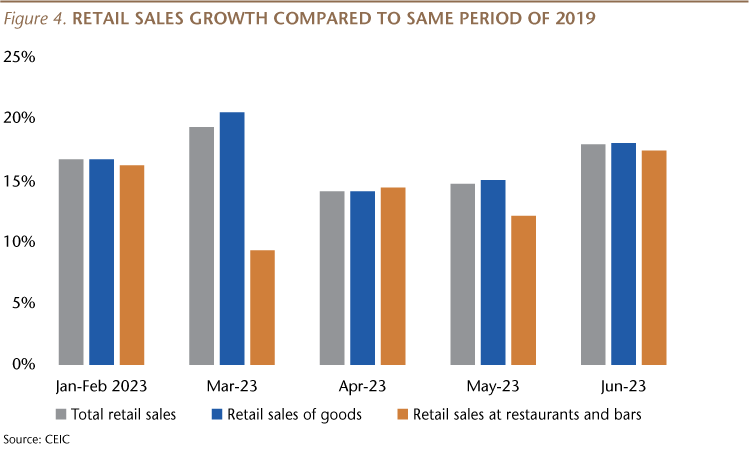

Spending on goods was weaker, but not terrible. Electric vehicle (EV) sales, for example, rose 35% YoY in the first half (and up 500% vs. 1H19).

Imports have been improving. The value of imports in June was 33% higher than in June 2019, up from 26% in May and 14% in April.

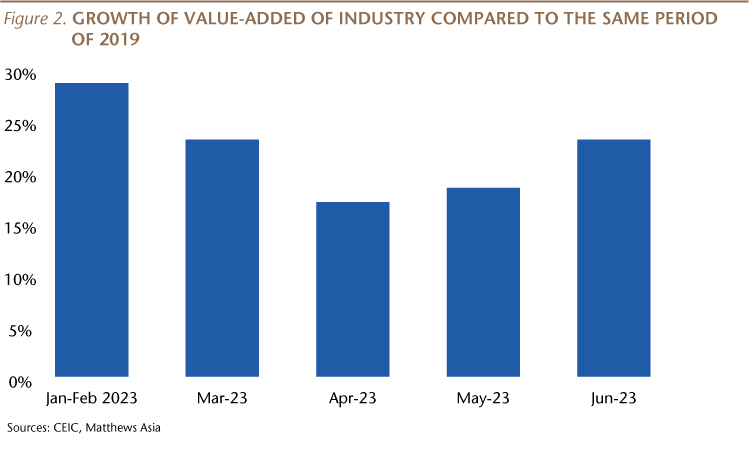

The industrial part of the economy remains quite weak, although there has been modest improvement recently, compared to pre-pandemic levels. Industrial value-added rose 23% in June, compared to four years ago, up from 18% in May and 17% in April. But we aren’t likely to see significant industrial improvement until next year.

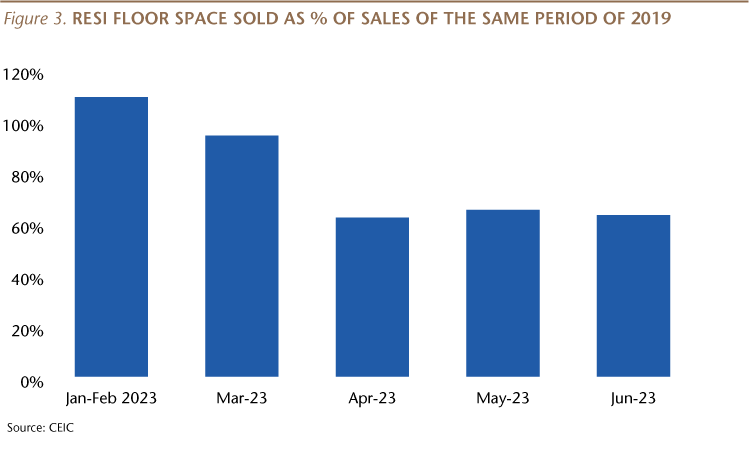

The residential property market is also weak, but not terrible. Sales are decelerating, but in the first six months of this year, new home sales on a square meter basis were equal to 78% of sales during the first six months of pre-pandemic 2019. In 70 large cities, new home prices in June were flat and down 1% compared to two years ago, but average prices are up 19% over five years and up 44% over 10 years. This is likely to improve towards the end of the year, as income growth continues, and confidence returns.

Overall, the economy is sluggish but not terrible, and household consumption seems to be gaining momentum the last couple of months, especially when compared to the same periods in pre-COVID 2019. Restaurant and bar sales, for example, in June were 17% higher than in June 2019, while May sales were 12% higher. Consumers are starting to shrug off their COVID trauma.

Solving for short-term problems

Why isn’t the Chinese economy doing even better? Two main reasons. First, China’s serious COVID trauma just ended in January, while Westerners got past COVID two years ago. And, Chinese consumers didn’t receive stimulus checks. Second, Chinese entrepreneurs are recovering from a two-year regulatory crackdown that crushed their animal spirits. This has hurt business and consumer confidence, since about 90% of companies and 90% of urban employment is with small, privately owned companies.

What can be done to fix these two problems? For getting over COVID trauma, the solution is time and patience. The recovery is clearly underway but may take two more quarters. When I was in Beijing in May, one official told me their analysis was that on average, it took other countries 15 months to get back to pre-COVID growth levels after the last wave of COVID cases. China is about half-way through that timeline.

There has been moderate easing: corporate lending rates are at all-time lows and mortgage rates are more than 100 basis points (1.0%) lower than a year ago. Mid- and long-term new lending to corporates last month was the highest level for June in history, suggesting business confidence may be in recovery mode. For repairing animal spirits, however, I think the solution isn’t a big monetary or fiscal policy stimulus.

No one I speak with in Beijing thinks a dramatic stimulus is coming, both because the government is concerned about higher debt levels, but also because there are doubts about how effective that would be in restoring confidence. Instead, in recent weeks, the government has ramped up a major rhetorical campaign to boost confidence among entrepreneurs. Yes, this is just talk, but animal spirits are weak because entrepreneurs (and consumers) are worried about the government’s attitude towards them, so this is likely an appropriate approach.

Remember what caused animal spirits to crash. It wasn’t an ideological attack on the platform companies or the broader private sector. It was the horrible execution of “common prosperity” policies designed to reduce inequality in income and unequal access to health care, housing and education. In an October 2021 Sinology, I explained:

One question at the top of mind for investors is, in what direction does the head of China’s Communist Party want to steer his country’s economy? In this issue of Sinology, we explain why it is unlikely that the recent regulatory crackdown is Xi Jinping’s attempt to roll back China’s private sector. Rather, we believe Xi is attempting to address the same socio-economic concerns that most democracies are wrestling with, although initial implementation has been chaotic. If the regulatory process is improved, and Xi succeeds in reducing inequality and strengthening corporate competition, he could lay a foundation for the next phase of China’s market-based development. If he fails, it would be because of poor implementation of policies designed to create “common prosperity,” not because he is anti-entrepreneur. We’ve already seen some negative consequences of poor implementation, but expect these to be resolved in the coming quarters.

What I got wrong was that it has taken more than a couple of quarters for Xi to acknowledge the disastrous execution of his “common prosperity” campaign and to course correct.

We finally saw that in July. The CCP Central Committee (the senior Party leaders) and the State Council (the top arm of the government) issued a joint statement on “promoting the development and growth of the private economy.” An official explained that there is “an urgent need” to address the problems facing private firms, and the document is intended to “boost confidence in the outlook for the private economy.” The document, which serves as guidance for central and local officials, describes the private sector as “a driving force behind promoting the Chinese path to modernization,” and states that the Party and government want to “promote a bigger, better and stronger private sector.” The document says Xi’s administration will support private firm research into “cutting-edge technology” and “support platform companies to excel in creating jobs.” The document also calls for “an atmosphere that encourages innovation and tolerates failure” and “enhances the sense of honor and social value of entrepreneurs.”

That was followed a few days later by a meeting of the top 24 members of the Central Committee, who reiterated support for entrepreneurs and platform companies. The Politburo acknowledged that China’s post-COVID economic recovery had been “torturous,” and declared that the Party would be taking steps to “promote private investment” and “invigorate capital markets and boost investor confidence.” The Party leaders said they want to support “healthy and sustainable development of platform companies,” and “encourage enterprises to dare to venture, dare to invest, dare to take risks, and actively create markets.”

These announcements from Party leaders followed other vows of support in July for private firms, especially the platform companies, which, remarkably, account for about one-quarter of urban employment. The NDRC, the lead planning agency, offered unusual support for platform companies - which include e-commerce, on-line car hailing, social media and digital finance – praising them for contributing to China’s technological self-reliance, and for bolstering “the quality and efficiency of the real economy.” The agency called out three major platform companies (Alibaba, Tencent and Meituan) for supporting economic development. At the same time, the Zhejiang provincial government signed a “comprehensive strategic cooperation agreement” with Alibaba, saying it would help the company “create innovative, competitive and leading digital technology.” And Xi’s deputy, Premier Li Qiang, met with representatives of major platform companies, praising them for “providing a new engine for innovation and development, providing new channels for employment and entrepreneurship, and providing public services.” The NDRC also announced steps designed to promote private investment.

While this policy course correction is long overdue, it is more likely to improve corporate and consumer confidence than any traditional stimulus, because it is designed to address concerns that Xi is no longer supportive of entrepreneurs. This is, of course, just talk, but I believe that Xi’s priority is restoring economic growth, and private companies, including the platforms, are China’s biggest employers, so I expect him to follow up with concrete actions. It will take time for entrepreneurs and consumers to respond. If investors are patient, they are likely to see more evidence of a gradual, consumer-led economic recovery in the coming quarters, as COVID trauma recedes and the government follows the leadership’s directive to get out of the way of business, allowing animal spirits to reemerge.

A return in confidence will be supported by continued accommodative monetary policy and high savings. Family bank balances have increased 63% from the start of 2020, as Chinese households were in savings mode during zero-COVID. The net increase in household bank accounts is equal to US$7.1 trillion, which is greater than the GDP of Japan in 2022, and equal to 125% of China’s 2019 retail sales. This is significant fuel for a continuing consumer spending rebound, as well as a recovery in mainland equities, where domestic investors hold about 95% of the market.

Structural challenges

Like all economies, China always faces long-term structural challenges. We’ve explored many of these in past issues of Sinology, from demographics to shadow banking and the absence of the rule of law. These problems are important and are among the reasons that China’s growth rate will continue to decelerate on a YoY basis, but Beijing’s track record in generating growth while managing them has been impressive. And, even if real, annual GDP growth were to average only 2% for the next 10 years (a much slower pace than I expect), the Chinese economy would expand by the equivalent of two Germanies.

Today, let’s look at a few challenges that are top of mind for investors.

Deflation is not on the horizon

China’s consumer price index (CPI) is low, but deflation is not a risk.

CPI was flat in June, down from 2.5% YoY a year ago, but this primarily reflects a sharp fall in global oil prices, rather than a general decline in the prices of goods and services in China (the definition of deflation).

Last June, West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil prices were up 61% YoY, leading to a 33% YoY rise in China’s vehicle fuel price index. This June, WTI was down 39% YoY, and China’s fuel index dropped 18% YoY, accounting for most of the fall in China’s headline CPI.

Keep in mind that in June, core CPI (ex-food and energy) in China rose 0.4% YoY, and services prices rose 0.7%. Low inflation, but not deflation. For the first six months of the year, core CPI rose 0.7% YoY, compared to 1% during the same period last year, 0.4% two years ago, and 1.1% three years ago.

Headline CPI may dip into negative territory for a short time before heading back up later in the year, and CPI is likely to be positive for the full year, although modest enough to permit China’s central bank to continue a moderately accommodative monetary policy.

Youth unemployment is embarrassing for Beijing

Weak industrial activity and private investment contributed to another challenge: the unemployment rate for urban youth (16-24) rose to 21.3% in June from 18.1% in February. This is the highest rate since the government began reporting this data in 2018.

Given that the unemployment rate for migrant workers was only 4.9% in June, the real problem is probably among recent college graduates.

Private firms have been slow to regain enough confidence to invest and hire, and the global tech slowdown has led to job cuts in China as well. As many as 30 million services jobs were lost during zero-COVID, and the rehiring pace has been gradual.

On top of that, the number of university graduates is expected to be over 11 million this year, up from 7 million a decade ago. The Chinese economy has long struggled to generate enough jobs that match the expectations of new grads, who faced a significant challenge to gain a university place.

High unemployment for these people is a problem, and is likely to remain so for many months, but these are China’s elite, and they are unlikely to express their frustration on the streets, which would jeopardize future employment prospects. The relatively small number of unemployed young people—about 6 million—means they are unlikely to be a significant obstacle to the gradual economic recovery we’ve been describing. Government policies that encourage state agencies and state-owned companies to hire more young people, as well as continued recovery in services jobs, may mitigate this problem in the coming months.

Debt levels serious, but low risk of a crisis

China’s debt problem is serious, but the risk of a hard landing or banking crisis is, in my view, low.

For context, China’s debt-to-GDP ratio in 2022, was 297%, according to the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), higher than that of Germany (190%) and the U.S. (256%), but below Canada (305%), France (334%) and Japan (414%).

It’s also worth noting that China’s gross savings rate, as a share of GDP, was 45% in 2021, higher than in Germany (31%), the U.S. (18%), Canada (22%), France (24%) and Japan (26%).

In China, potential bad debts are corporate, not household, and were made at the direction of the state, by state-controlled banks to state-owned enterprises (SOEs). This provides the state with the ability to manage the timing and pace of recognition of nonperforming loans. It is also important to note that the majority of potential hidden bad debts are held by state-owned firms, while the leverage of the privately owned companies that employ the majority of the workforce and account for the majority of economic growth isn’t high.

A large share of SOE debt is related to local government finance vehicles (LGFVs). And in China, local governments are all effectively branch offices of the central government, in contrast to the U.S., where there is a clear separation between the financial obligations of local, state and national authorities. This is consistent with my view that the vast majority of China’s debt is owed to state-controlled banks by state-controlled entities, including SOEs and LGFVs. As a result, while the debt burden is significant, the risk of default or systemic crisis is not, especially given that the state-controlled banking system is very liquid.

Cleaning up China’s debt problem will be expensive, and does limit the government’s options for fiscal stimulus, but will not likely lead to the dramatic hard landing or banking crisis scenarios that make for a sexier media story.

Industrial policy response to those challenges

One of the government’s efforts to stimulate growth and mitigate the impact of those challenges has been the use of industrial policies to promote new sectors. Some of these policies have been successful, so it is likely that Beijing will continue down this path. For example, industrial policies have resulted in China becoming the world’s largest producer, consumer and exporter of electric vehicles, and accounting for two-thirds of global EV battery production, as well as about 80% of global solar panel production. China is on track to surpass Japan as the world’s largest auto exporter in 2023, after edging out Germany last year.

U.S. – China relations: strained, but crisis unlikely

The political relationship between Washington and Beijing is likely to remain strained, but a crisis is unlikely, especially after the Biden administration has recalibrated its approach to China in recent months.

The administration’s rhetoric has been more constructive since an April speech by Treasury Secretary Yellen, suggesting that Biden concluded that his team’s more aggressive approach to China was producing dangerous consequences and needed to be altered, despite the domestic political risks during the campaign season.

In April, Yellen said that the U.S. does not seek to decouple from China and wants a relationship that “fosters growth and innovation in both countries.”

Secretary of State Blinken continued this more constructive approach on a visit to Beijing in June, where he echoed Yellen’s comment, saying that “healthy and robust economic engagement benefits both the U.S. and China,” and that “China’s broad economic success is also in our interest.”

Blinken also reassured China on cross-Strait relations, stating, “We do not support Taiwan independence.” This has been U.S. policy for decades, but recently, senior American officials have often neglected to say this when citing the catechism of the U.S. one-China policy, which has fueled much anxiety in Beijing.

Yellen reenforced these messages during a July trip to Beijing, saying, “President Biden and I do not see the relationship between the U.S. and China through the frame of great power conflict. . . We believe it is possible to achieve an economic relationship that is mutually beneficial in the long term—one that supports growth and innovation on both sides.”

To be clear, I do not expect a significant improvement in the relationship through the end of next year, given the U.S. political cycle. The administration’s goals are quite limited, as Blinken explained on July 23: “We are working to put some stability in the relationship, to put a floor under the relationship.”

But, given that I also expect Xi to continue to take a pragmatic approach to the relationship, the administration’s recalibration, which has led to more bilateral communication, will hopefully restore some trust. While this won’t make the relationship much better in the near term, it should stabilize it, reducing the risk that an accident spirals into a crisis that neither side desires.

Finally, political and trade tensions are unlikely to disrupt the Chinese economic recovery. China is sending less of its goods to the U.S. but has gained market share elsewhere. China’s share of global exports in 1Q23 was 14%, compared to 12.8% in 2017, before the Trump tariffs. More importantly, domestic demand is the primary growth engine in China.

My glass is still half-full

I know it’s unfashionable to be optimistic about China’s economy, but I hope this note has given readers an opportunity to think about how the consensus view may be too negative.

Future issues of Sinology will keep you updated on whether time and policy pragmatism have led to stronger consumer spending and entrepreneurial animal spirits.

Andy Rothman

Investment Strategist

Matthews Asia