What Is Xi Jinping Thinking?

In this issue of Sinology, we explain why it is unlikely that the recent regulatory crackdown is Chinese Party chief Xi Jinping’s attempt to roll back China’s private sector.

SubscribeIf the regulatory process is improved, and Xi succeeds in reducing inequality and strengthening corporate competition, he could lay a foundation for the next phase of China’s market-based development. If he fails, it would be because of poor implementation of policies designed to create “common prosperity,” not because he is anti-entrepreneur.

One question at the top of mind for investors is, in what direction does the head of China’s Communist Party want to steer his country’s economy? In this issue of Sinology, we explain why it is unlikely that the recent regulatory crackdown is Xi Jinping’s attempt to roll back China’s private sector. Rather, we believe Xi is attempting to address the same socio-economic concerns that most democracies are wrestling with, although initial implementation has been chaotic. If the regulatory process is improved, and Xi succeeds in reducing inequality and strengthening corporate competition, he could lay a foundation for the next phase of China’s market-based development. If he fails, it would be because of poor implementation of policies designed to create “common prosperity,” not because he is anti-entrepreneur. We’ve already seen some negative consequences of poor implementation, but expect these to be resolved in the coming quarters.

A “common prosperity” regulatory storm

A storm of regulatory changes have roiled many parts of the Chinese economy in recent months, stalling the property market, shutting some after-school tutoring businesses, pausing the launch of online games, and creating electricity shortages. Economic growth, while still rapid, has slowed, and foreign investor sentiment has been sapped. Party officials waited a long time before attempting to explain the rationale behind the regulatory storm, and even then, many foreign investors were left wondering, “What is Xi Jinping thinking?”

Two main schools of thought have emerged in the foreign investment community. One says that Xi wants to roll back the market-based reforms of the past few decades. The second believes that rather than an attempt to curb the private sector, Xi’s regulatory changes are part of an effort to address important socio-economic concerns, including income inequality and unequal access to education and health care.

SCHOOL ONE: ROLLING BACK THE ENTREPRENEURIAL TIDE

The first view is that the regulatory storm is part of an effort to roll back the market-based reforms of the past few decades, including restricting the ability of entrepreneurs to innovate. Some even posit that Xi wants to return China to its Maoist past, when private enterprise was banned.

In my view, this perspective is based on the uncertainties caused by the rapid and chaotic roll out of new regulations, rather than on the long-term objectives announced by leaders of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Market-based reforms and the private sector have created the economic growth which has kept the CCP in power for far longer than most other one-party, authoritarian regimes. Reversing these reforms would destroy China’s economy, which would destroy popular support for the CCP. Why would Party leaders take what would clearly be a politically suicidal path?

The Chinese economy has boomed

In recent decades, the Chinese economy has boomed.

In 1980, when I first visited China as a student, its per capita GDP was less than that of Afghanistan, Haiti and Bangladesh, and 43% of China’s population was living below the World Bank’s poverty line. Today, Chinese consumers are estimated to account for 20% of global luxury sales.

And the boom benefited the overwhelming majority of the country, not just consumers of luxury goods. “The Chinese transformation is a unique event in world economic history: never have so many people over such a relatively short period of time increased their income so much,” according to a recent study by economists Branko Milanovic, Filip Novokmet and Li Yang. They found that “it took the UK about a century-and-half to increase its GDP per capita by half as much as China did in less than 40 years” and “it took the United States 240 years . . . do what China accomplished in 40 years.”

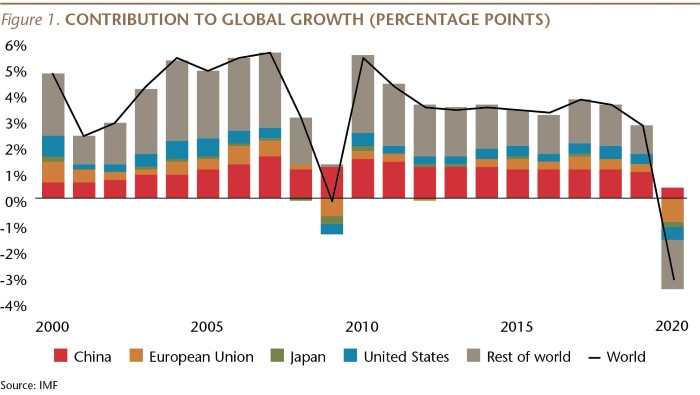

The global impact has been dramatic. In the 10 years through 2019, China, on average, accounted for about one-third of global economic growth, larger than the combined share of global growth from the U.S., Europe and Japan. In 2020, China was the only major economy to register growth.

The boom has been driven by market-based reforms and entrepreneurial companies

How was this boom achieved? “The answer is straightforward,” according to economist Barry Naughton. “Market-oriented economic reforms are what actually shaped development.”

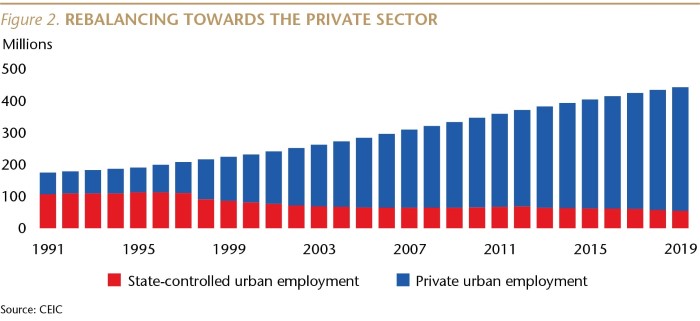

The evidence of market-based reforms is clear. When I returned to China in 1984 as a junior American diplomat, there were no private companies—everyone worked for the state. Today, almost 90% of urban employment is in small, privately owned, entrepreneurial firms. With the state-sector continuing to shrink, all of the net, new job creation today comes from private companies.

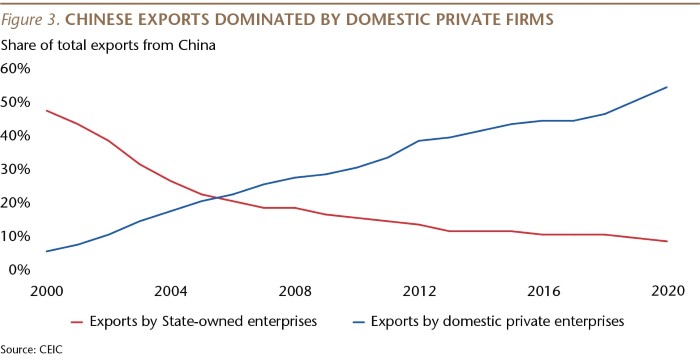

Another way to visualize the rise of private companies is through their share of China’s exports. Just 20 years ago, domestic private companies accounted for only about 5% of total exports, while in 2020 that share rose to more than 50%. In contrast, over that period of time, the share of exports from state-owned enterprises (SOEs) fell from 47% to less than 10%. (The balance of exports are produced largely by foreign-owned firms.) Even though exports play a smaller role in the country’s growth, China remains the world’s largest goods exporter—so the dominant share held by private firms is a useful metric for understanding the key role entrepreneurs now play.

A recent study published in the U.S. by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that in 2019, individuals owned 69% of registered capital of all Chinese companies, up from a 52% share in 2000.

Privately owned companies are China’s most innovative firms and the government’s economic growth plans are based on innovation. Vice Premier Liu He recently acknowledged private companies account for “more than 70% of technological innovation.”

The two largest, publicly listed Chinese companies, by market cap, are privately owned. Privately owned firms also account for about 80% of companies listed on China’s Shanghai science and technology innovation (STAR) board, its version of NASDAQ.

The Party has also supported innovation with investment in education. The annual number of graduates with college and advanced degrees has risen to 8.7 million in 2020, up from 1 million in 2000. Most of these new graduates will take jobs in the private sector.

The rise of China’s private sector has continued under Xi Jinping. Since he became head of the Party in 2012, private firms have continued to drive all net, new job creation. Real (inflation-adjusted) income growth has risen at an average annual pace of 6.4%, compared to 2.3% in the U.S. and 1.5% in the UK. China’s per capita GDP, on a purchasing power parity (PPP) basis, was 27% of the U.S. in 2020, up from 19% in 2012. Entrepreneurial, privately owned companies have fueled this growth.

The Party has taken a very pragmatic and practical approach to economics and business since the 1990s. Rolling back this market-based approach would devastate Chinese job creation, innovation and wealth. What would motivate the Party leadership to take that path?

The Party hasn’t said it wants to curb entrepreneurs

It would, in my view, be illogical and counterproductive for the Party to want to roll back the country’s entrepreneurial spirit. And, this is not what Party leaders have said they want to do.

In an August 17 speech to the Party’s Central Committee of Finance and Economics, Xi said he wants to “enhance the ability to get rich.” In that speech, the text of which was only made public on October 15, Xi said, “Small and medium-sized business owners and self-employed businesses are important groups for starting a business and getting rich.” He added that “It is necessary to protect property rights and intellectual property rights, and protect legal wealth.”

Han Wenxiu, a senior Party official responsible for financial and economic policy, said promoting “common prosperity” does not mean “killing the rich to help the poor.”

The Party says it won’t sacrifice growth

Party officials have also said that they do not intend to sacrifice growth in order to achieve “common prosperity.”

According to Han Wenxiu, the Party will “guard against falling into the trap of welfarism. . . We cannot support layabouts.”

Xi, in his August speech, said, “The common prosperity we are talking about . . . is not the prosperity of a few people, nor is it uniform egalitarianism.”

Xinhua, an official state media outlet, declared that, “Common prosperity is . . . by no means robbing the rich to help the poor, as misinterpreted by some Western media. Protecting legitimate private property has been written into China’s constitution.” The editorial said that the government’s aim is “far from simply redistributing wealth,” and is about “creating more inclusive and fair conditions for people to get a better education and improve their development capabilities.”

Another senior Party economist, Xie Fuzhan, writing in the official People’s Daily, declared that Xi Jinping’s plan is to “divide the cake well in the process of continually enlarging the cake.”

SCHOOL TWO: TRYING TO SOLVE SOCIO-ECONOMIC PROBLEMS

Rather than an attempt to curb the private sector, the CCP’s regulatory changes are an effort to address the same socio-economic concerns that most democracies are wrestling with, according to the second school of thought. Everything from income inequality to unequal access to education and health care.

Since the 1980s, many of China’s economic reforms have been modeled after the American experience, including supporting industrial development with public infrastructure and trade barriers to protect nascent sectors. The Party has also drawn lessons from American policy failures. In real estate, for example, Chinese regulators have required homebuyers to put down a lot of cash and have limited mortgage securitization.

Recently, Xi has observed that rising inequality in the U.S. led to social and then political polarization, which led to government stalemate over measures to resolve those problems. In his August speech, Xi said, “Some countries are divided between the rich and the poor, and the middle class has collapsed, leading to social tearing, political polarization, and populism. The lessons are very profound!”

We’re all familiar with the socio-economic challenges faced by many democratic nations with mature economies. Evan Osnos, in his new book, Wildland: The Making of America’s Fury, describes some of the issues that I believe have resonated with Xi:

“Many wealthy Americans justified those gaps by hailing America’s classic faith in upward mobility—the prospect that all could achieve success. But reality no longer matched the myth. On average, 90 percent of American children born in 1940 grew up to earn more than their parents, but by the early twenty-first century, that number had sunk to 50 percent. Mobility was getting swamped by inequality because wealthy families could pay for so much that extended their lead—private SAT tutors, political influence, exclusive investments, and tax advice. The further they pulled ahead, the more likely their children were to go to elite schools, meet similar spouses, and circulate in networks that delivered further access. For all the pride and inspiration wrapped up in notions of the American Dream, the World Bank had calculated that, by 2018, the United States had a lower level of intergenerational mobility than China.”

Xi is concerned that although China has gotten much richer, it faces inequality problems similar to those in the U.S. For example, according to China’s central bank, 10% of households own 58% of the nation’s financial assets. Not yet as high as in the U.S., where the top 10% hold 80% of financial assets, but arguably high enough to cause concerns among Chinese leaders. “There is a large gap between urban and rural regional development and income distribution,” Xi noted in his August speech.

“Over the past two decades, China has seen a sharp reduction of poverty, but also a substantial increase of inequality,” according to a working paper by IMF economists. “Despite significant progress, China also faces considerable inequality in opportunities, such as completion of higher tertiary education and access to certain financial services. While China managed to drastically increase secondary and tertiary enrolment ratios since the 1980s, in 2010, tertiary education was more unequally distributed than in other emerging and advanced economies on various dimensions, including based on regional, rural-urban and wealth differences.”

About 36% of China’s population is rural (down from 80% in 1960, and compared to 17% in the U.S.), and while access to education has improved significantly, serious challenges remain. Stanford University’s Scott Rozelle, in his recent book, Invisible China, reports “studies consistently show a large and persistent gap in learning between children in China’s rural and urban schools.” He notes that “a third of rural sixth graders need glasses but don’t have them,” and in some rural communities, “on average, more than 50% of these children were shown to have delays in cognition, language or social-emotional skills.”

China’s version of LBJ’s “Great Society”?

Some of the recent rhetoric from Chinese leaders echoes that of American politicians, past and present.

President Lyndon Johnson outlined his vision of broad socio-economic reforms in a 1964 speech:

“For a century we labored to settle and to subdue a continent. For half a century we called upon unbounded invention and untiring industry to create an order of plenty for all of our people. The challenge of the next half century is whether we have the wisdom to use that wealth to enrich and elevate our national life, and to advance the quality of our American civilization. . . we have the opportunity to move not only toward the rich society and the powerful society, but upward to the Great Society.”

Xi’s concerns about these socio-economic issues are not new. Back in 2015, he and other senior Party leaders issued a statement calling for steady progress “in the development of common prosperity,” stressing “fairness of opportunity,” steps to “reduce income disparities,” and “plans for the entire population to become insured.”

In 2017, Xi said that as China’s economy has matured and become wealthier, the “principal contradiction” facing its society had changed. With poverty largely eliminated, "What we now face is the contradiction between unbalanced and inadequate development and the people's ever-growing needs for a better life.”

More recently, Xi said, “We cannot permit the wealth gap to become an unbridgeable gulf.”

Echoes of President Joe Biden’s recent statement that “Millions of Americans lost their jobs last year while the wealthiest 1 percent of Americans saw their net worth increase by US$4 trillion. It just goes to show you how distorted and unfair our economy has become. It wasn’t always this way.” Or Senator Marco Rubio’s comment that, “Our nation does not exist to serve the interests of the market. The market exists to serve our nation and our people.”

Xi said, “Strengthening anti-monopoly and in-depth implementation of fair competition policies are the inherent requirements . . . [to] create a broad development space for various market entities, especially small and medium-sized enterprises, and better protect consumer rights and interests.”

Biden said, “Excessive market concentration threatens basic economic liberties, democratic accountability, and the welfare of workers, farmers, small businesses, startups, and consumers . . . [we will] enforce the antitrust laws to combat the excessive concentration of industry, the abuses of market power.” And Rubio said, “We reward and incentivize certain business practices that promote economic growth. But it’s growth that often solely benefits shareholders, at the expense of new jobs and better pay.”

Xi recently declared, “Let the internet better benefit the people.” While Biden said, “A small number of dominant internet platforms use their power to exclude market entrants, to extract monopoly profits, and to gather intimate personal information that they can exploit for their own advantage.” On this topic, Rubio said, “Big Tech has destroyed countless Americans’ reputations, openly interfered in our elections by banning news stories, and baselessly censored important topics like the origins of the coronavirus.”

A long history of more government intervention in the economy

The Party’s concern about “common prosperity” is not new. Nor is the Party’s inclination to use a more visible hand to guide economic development. Since the early reform days, China has taken a more European, rather than American approach to capitalism. (And, as Milanovic, Novokmet and Yang note, “It is a unique feature of the Chinese transformation that it has been carried out under the authoritative aegis of the CCP, which has retained its political monopoly against the background of market reforms and economic decentralization.”)

General government intervention was often designed to support workers. During the decade from 2005 to 2015, the minimum wage was raised by a double-digit rate each year, with the Party seeming to say that it didn’t value jobs that would not pay a living wage.

For a long time, government intervention in specific sectors usually supported state-owned firms, such as funding for development of a civilian jetliner, nuclear power plants, electricity transmission and mobile broadband telecom. But, more recently, some intervention has benefited entrepreneurs.

In 2006, for example, the government enacted a renewable energy law, providing incentives for privately owned firms to develop the photovoltaic industry. Now, China is the world’s largest producer of solar panels, and all of the 10 largest Chinese manufacturers are privately owned.

In 2012, the government announced new policies to support production of new energy vehicles. Now, China is the world’s largest manufacturer of electric vehicles, and many of the producers are privately owned.

The visible hand of the government also reached in when Party leaders felt that entrepreneurs were taking too many risks. Peer-to-peer (P2P) lending was lightly regulated and boomed in the late 2000s, but then thousands of firms failed, leading the government to shut down almost all of the remaining lenders. This was accompanied by a broad effort to reduce risks in the financial system, and, through September, the outstanding balance of off-balance-sheet (shadow) lending declined year-over-year for 40 consecutive months.

Accelerated intervention now

In recent months, the scope and pace of government intervention in the economy has accelerated significantly. I think there are several reasons for this acceleration.

Economist Barry Naughton, at the University of California, San Diego, notes that for China, a key lesson of the Global Financial Crisis was that “robust and decisive government intervention could and should complement the market economy.”

As noted earlier, Xi has been talking about policies designed to promote “common prosperity” since soon after he became Party chief in 2012, and a series of modest regulatory steps were taken every year since that time. Cracking down on kids’ exposure to online gaming, for example, or on the sale of expensive liquor, or on drug pricing. In each case, better companies adapted their business plans and thrived in the new regulatory environment.

But, overall progress towards “common prosperity” was limited, and Xi may have become alarmed as he watched similar socio-economic problems lead to increased social and political polarization in many developed countries. Often, those governments struggled to address the problems of inequality. Sometimes, the problems led to social unrest.

Xi may have wanted to act more aggressively a few years ago, but he may have held back as trade war rhetoric and aggressive tariff increases by Washington raised concerns over the ability of the Chinese economy to absorb the short-term, negative side-effects of new regulations. Then, just as it was clear that the tariffs had little impact on China, COVID-19 emerged.

The current regulatory push may reflect a calculation by Xi that China’s economy is now healthy and stable enough to manage the changes. On April 30, he said he saw a “window of opportunity” to make changes as the economy had largely recovered from COVID. In August, Xi said, “A well-off society has created good conditions for promoting common prosperity.”

Xi probably also wants to have the policy elements of his “common prosperity” program underway before next fall’s 20th Party Congress, when the broader CCP leadership is likely to grant him a third, five-year term.

Potential benefits to regulations intended to promote prosperity

If the regulations designed to promote “common prosperity” are implemented in a reasonably effective way, there are significant potential benefits for the Chinese economy, and, therefore, for the Party.

If income inequality is reduced, and access to health care and education improved, the longer-term risk of social and political instability would be reduced.

Higher wages for low-skill workers would support domestic consumption, the largest part of the Chinese economy.

Curbing anti-competitive practices by larger firms would support development of small and medium-sized firms, which employ the majority of China’s workforce.

Reducing uncertainty about the regulatory environment, by, for example, making clear what constitutes anti-competitive practices, would enable companies to adjust their business models with more confidence.

Potential risk: will regulation kill entrepreneurial spirit and innovation?

If we accept, for the reasons spelled out earlier, that the Party is not deliberately trying to handicap China’s private sector, how worried should we be that the new regulatory environment might inadvertently kill the nation’s entrepreneurial spirit and innovation?

To answer this question, let’s start by acknowledging that most Chinese citizens have a generally positive outlook on the visible hand of the government. Naughton explains it this way:

“One of the many differences between the mind-set of the average Chinese and that of the average American involves judgments about the ability of government to shape the future. Many Americans express feelings of passivity and helplessness in the face of impending technological change and are deeply skeptical of the ability of government to change or shape the future. By contrast, many Chinese seem to assume that government will shape the future and accept that government “knows more” about the future than they do. As a result, they tend to passively or actively support the idea that their government will steer the economy into the future. Of course, the difference in mind-set is easily traced to the contrasting experiences of economic growth over the past forty years: while the median American wage has stagnated, household incomes in China have doubled each decade. Both Chinese and Americans have experienced disorienting technological change over the past two decades, but the experience for Chinese has been overwhelmingly positive. Projecting their recent pasts into the future, it is no surprise that Chinese residents are more upbeat about the future and receptive to grand government schemes than are ambivalent Americans.”

Most Chinese entrepreneurs are less wary than their American counterparts of intervention by the state, so the regulatory changes do not seem alarming to them.

Chinese entrepreneurs understand that the Party will support their efforts to create jobs and get rich, as long as the entrepreneurs accept that they cannot use their wealth and fame to challenge the Party on political and governance issues. (Unsurprisingly, the Party recently intervened after two well-known private companies questioned or ignored the advice of regulators.)

Since 2000, entrepreneurs have even been welcomed into the CCP’s membership ranks, after then Party chief Jiang Zemin developed a theory (the “Three Represents”) which eliminated any ideological barriers to the Communist Party embracing capitalists.

This embrace helped both groups. Entrepreneurs thrived, created jobs and wealth, and became the engine of China’s economic growth. Some of them joined the Party, which also thrived, and became wealthy.

In a study of data for the period between 1988 and 2013, Milanovic, Novokmet and Yang documented the transformation of China’s urban elite, which they define as the top 5% of the urban population in terms of their per capita disposable income. They found that China “transformed itself from a society where workers and employees, most of whom linked to the state, accounted for three-quarters of the elite to a situation where private sector business people and professionals are the majority of the new elite.” It is likely that transformation has continued in more recent years.

It is also likely that most entrepreneurs will accept and adapt to the Party’s new regulations, just as they have in the past. It appears that Chinese investors already have. This year, the main domestic equity index has far outperformed global China indexes, which are dominated by foreign investors.

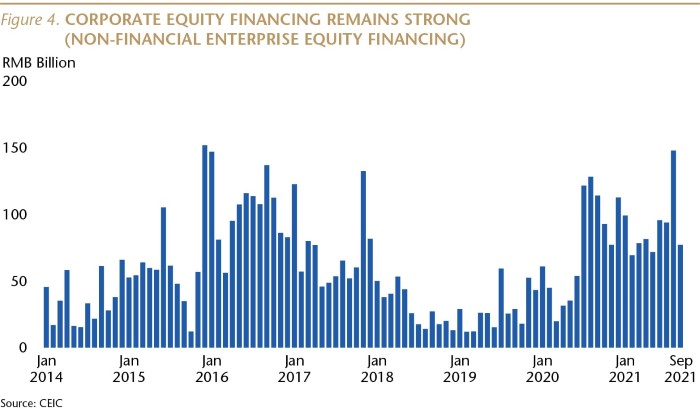

Equity fundraising in China’s domestic markets also remains strong this year, and may come close to matching the 2016 historic peak.

Global venture capital (VC) investors have also not been deterred by the regulatory changes. Research firm Preqin reports that VC investment in Chinese startups has not slowed in recent months, and the US$84.8 billion invested during the first nine months of the year is nearly equal to the US$86.1 billion invested in all of 2020.

The biggest risk: will poor implementation inadvertently slow growth?

The risks from Xi Jinping’s “common prosperity” regulatory changes do not come from his objectives, which are focused on reducing inequality, rather than rolling back market-based reforms. The biggest risk is that the regulations designed to achieve these admirable objectives will be poorly implemented, creating unintended negative consequences which inhibit private sector job creation and economic growth.

One concern is that because the Chinese government can act quickly, without the checks and balances of opposition parties and the transparency created by a free press, it often fails to clearly articulate its policy objectives, leading to uncertainty and confusion.

The Party leadership has acknowledged this misstep, with a blizzard of statements and speeches explaining their objectives, but only months after launching the regulatory changes.

Still, as noted earlier, uncertainty and confusion was greatest outside of China, an audience of only secondary concern to the Party.

More worrisome is that the regulations are often written by central government officials who don’t have commercial experience, and with little input from the business community. These regulations are then implemented by local officials who are given firm political mandates and little flexibility to respond to market conditions. Moreover, regulations from different departments often overlap without careful consideration of how the combined impact may effect an industry.

The current electricity shortage across China is a good example. Several “common prosperity” policies were launched recently, all with admirable objectives: improving coal mine safety; reducing corruption in the coal industry; raising energy efficiency; and reducing emissions. But the impact of local officials pushing hard to meet their performance targets in all of these areas at the same time, combined with rising demand for power as manufacturing rebounded from COVID, while weather conditions limited production from hydro and wind generators, created a perfect regulatory storm.

Once the negative consequences of this regulatory storm became clear, central officials responded predictably, instructing local governments to soften implementation of new regulations and prioritize coal production and electricity generation. The admirable objectives have not been abandoned, but will be pursued in a less aggressive way that (hopefully) does not create more unintended chaos.

Recently, Party officials acknowledged that “common prosperity” needs to be pursued in a more incremental way to reduce the risk of unintended consequences. “Common prosperity is a long-term goal,” Xi declared in August. “It requires a process and cannot be achieved overnight.” He called for “substantive progress” by 2035.

CCP economist Xie Fuzhan said they will focus on “accumulating small victories” on the path towards “decisive victory,” and he warned against “overdoing it.”

China’s Leninist political system is prone to “overdoing it.” But, in the economic sphere, Party leaders seem aware of this problem and are generally quick to change course to prevent short-term negative consequences from derailing longer-term growth. The last few decades of macro data reflect the Party’s ability and willingness to course-correct on economics.

This is why I think the highest probability is for near-term uncertainty and volatility, while the Party fine-tunes its regulatory approach. But in the longer run, even imperfect efforts to reduce the socio-economic strains most nations are facing are likely to improve the odds of healthy economic growth and social stability in China.

I anticipate this uncertainty and volatility will extend into the first quarter of next year, when the regulatory environment will be clearer, allowing companies to adjust their business models, and activity to return to normal. In the meantime, foreign investors are likely to remain wary.

Andy Rothman

Investment Strategist

Matthews Asia

Resources:

- Yang, Li; Novokmet, Filip; Milanovic, Branko. From Workers to Capitalists in Less Than Two Generations: A Study of Chinese Urban Elite Transformation Between 1988 and 2013. February 2020. https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/enbxv/

- Naughton, Barry. The Rise of China’s Industrial Policy, 1978-2020. 2021 https://dusselpeters.com/CECHIMEX/Naughton2021_Industrial_Policy_in_China_CECHIMEX.pdf

- Fateful Decisions: Choices That Will Shape China’s Future. Edited by Thomas Fingar and Jean C. Oi, Stanford University Press. 2020.

- Rozelle, Scott; Hell, Natalie. Invisible China: How the Urban-Rural Divide Threatens China’s Rise. University of Chicago Press. 2020

- Sonali Jain-Chandra; Khor, Niny; Mano, Rui; Schauer, Johanna; Wingender, Philippe; Zhuang, Juzhong. Inequality in China—Trends, Drivers and Policy Remedies. IMF, 2018. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2018/06/05/Inequality-in-China-Trends-Drivers-and-Policy-Remedies-45878

- Osnos, Evan. Wildland: The Making of America's Fury. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. 2021.

- Text of Xi Jinping’s August 17, 2021 speech on common prosperity. http://www.qstheory.cn/dukan/qs/2021-10/15/c_1127959365.htm