A Roadmap for Continued Economic Reforms

China’s 19th Congress of the Communist Party this week upheld several important trends, including the ideological authority of Xi Jinping—a powerful, but not dictatorial, leader.

"China’s leadership meeting reconfirmed several important trends. Xi Jinping is a powerful leader, but he is not a dictator."

This week’s meeting of China’s ruling elite reconfirmed several trends which are important for global investors. Xi Jinping is the strongest Chinese leader since Deng Xiaoping, but he is not a dictator. There will not be significant changes to economic policy, with Xi continuing to emphasize quality over quantity; gradual progress toward a more market-driven, entrepreneurial economy; and financial sector derisking. Xi will play a more visible role on the global stage, taking the opportunity to step up where Washington steps back, including on climate change.

The 19th Congress of the Chinese Communist Party, a twice-a-decade event, wrapped up this week, providing a roadmap for economic policy during Xi Jinping’s second five-year term as Party chief. In this issue of Sinology, we discuss the key takeaways in the areas of politics, economics and foreign policy.

Politics: Xi is strong, but not a dictator

Xi Jinping clearly consolidated his political power over the past few years, a process which was formally recognized at the Congress. His personal political philosophy, “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era,” was enshrined in the Party constitution as part of its “guiding ideology,” along with “Marxism–Leninism–Mao Zedong Thought” and “Deng Xiaoping Theory.” Xi’s two immediate predecessors as Party chief, Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, had their philosophies added to the Party constitution but without reference to their names. Xi is clearly the most powerful leader since Deng died in 1997.

There are, however, clearly limits to Xi’s power within the Party. Wang Qishan, one of his closest confidents and director of Xi’s anti-corruption campaign, was forced to retire from the Politburo Standing Committee this week, having reached the Party’s informal retirement age. There was widespread speculation that Xi hoped to persuade his colleagues to break with past practice and permit Wang to remain in the leadership, but that did not happen.

It is important to acknowledge that in addition to enhancing his power as head of the Party, Xi has been working to strengthen the Party and its control over China’s economic and political infrastructure. Unique among one-party, authoritarian regimes, since 1989 there have been three peaceful, efficient transfers of power between leaders, none of whom was from the same family.

The Party this week broke with recent precedent and did not anoint a successor to Xi. There is not, however, enough visibility into internal Party politics for us to understand what this means. One possibility is that Xi is aiming to ignore the retirement rules and stay on for a third term. It is also possible that Xi will retire in five years, but does not want to be a lame duck leader, with his successor watching over his shoulder throughout that time. It is worth keeping in mind just how opaque the Chinese political process is. Five years ago, just ahead of the last Congress, Xi—who was expected to be anointed Party chief at that meeting—disappeared from public view for two weeks, skipping meetings with Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and the leaders of Denmark and Singapore. There was much media speculation, including reports that Xi was injured in an assassination attempt or had suffered a heart attack. We still don’t know what really happened back then, but it clearly did not signal Xi’s political (or physical) weakness.

Economics: Focus on Quality over Quantity

One of the most significant developments of the Congress was the decision to change (for the first time since 1981) the Party’s mission statement, or in Party jargon, the “principal contradiction facing Chinese society.”

In 1981, the Party’s mission was to bridge the gap between people’s material needs and insufficient goods to meet those needs. That kicked off three decades of policies intended to achieve the fastest growth and the greatest industrial output possible. China’s amazing economic boom followed, but the negative consequences of that approach are well-documented.

During the just-concluded Congress, Xi explained why the Party’s mission statement had to be revised to focus on the quality of growth, rather than just on the speed of growth and quantity of output. “The principal contradiction facing Chinese society has evolved . . . What we now face is the contradiction between unbalanced and inadequate development, and the people’s ever-growing needs for a better life. . . Not only have their material and cultural needs grown; their demands for democracy, rule of law, fairness and justice, security, and a better environment are increasing.”

While Xi is not proposing to adopt Western-style rule of law or representative democracy, he is reaffirming his commitment to dealing with inequality in income, health care, education and pensions, as well as the consequences of horrific air, water and soil pollution.

This is not a new focus for Xi, as government spending on all of these programs rose at double-digit annual rates during his first term. But Xi has confirmed that these issues will remain priorities during his second term.

In our view, when Xi referred to the economy “transitioning from a phase of rapid growth to a stage of high-quality development,” he was signaling that he will continue to pursue supply-side reforms, primarily reducing overcapacity and debt levels among state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in heavy industry. In the previous issue of Sinology, we noted that some progress has been made in that area, with significant reductions in the number of steel and coal workers, and stabilization of SOE debt levels.

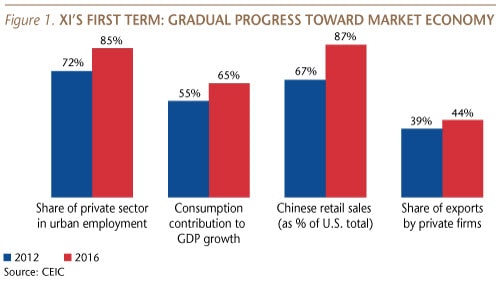

We tend to focus more on what politicians (in any country) do, rather than what they say. And over the last five years, the role of SOEs has continued to shrink while the role of China’s entrepreneurs has continued to rise. The Chinese consumer, fueled by incredible income growth, has also surpassed industry as the primary economic engine. So even though Xi praised the role of SOEs, we put more weight on his talk of developing “an economy with more effective market mechanisms, dynamic micro-entities, and sound regulation,” and his pledge to “stimulate and protect the spirit of entrepreneurship.”

We also think it is significant that Liu He, Xi’s top economic advisor, and a strong proponent of market-based reforms, was promoted to the Party’s senior ranks this week. Additionally, while five heads of major SOEs were in the Party’s leadership during the last Congress, no SOE representatives are in the current political lineup. This is the first time in at least 15 years that SOEs have not had a representative on the Party’s Central Committee.

Xi mentioned the residential property market in his speech, reiterating his government’s principle that “housing is for living, not for speculation.” This, too, is not new, and is consistent with our view that the government will continue tapping on the policy brakes, but will not take dramatic steps. As we noted in our previous issue of Sinology, since the start of 2011, prices are only up by 13% in China’s smaller cities, which account for two-thirds of the country’s new home sales. Nominal income, meanwhile, has risen by about 10% every year. And even if new home sales are flat year-on-year in 2018, most Chinese would still buy an estimated total of more than 12 million homes with a lot of cash down.

Xi also confirmed that he will continue his anti-corruption campaign, which Xinhua, China’s official news agency, described this week as an effort “to secure a sweeping victory over the greatest threat to the Party.”

Overall, we expect few significant changes to economic policy in the coming quarters.

Foreign Policy: Searching For a Bigger Role on the World Stage

Xi made clear that he intends to play a larger role on the world stage in the coming years. He said that China’s economic success provides an alternative model to developing countries, and sharing this experience with other nations is part of the “great rejuvenation of China.”

Xi’s plan is somewhat opportunistic: where Washington is retreating from the global arena, he hopes to step up. For example, Xi pledged China would continue to embrace globalization and trade, and he also expressed a desire to lead international efforts to respond to climate change.

But we do not anticipate Xi will become more antagonistic toward his regional neighbors or the U.S., recognizing that his recent aggressive moves have been counterproductive. For example, to manage the North Korea problem, Xi is likely to continue working cooperatively with Washington, largely because he values a positive relationship with President Trump. We will have a better perspective on U.S.–China relations after Trump’s early November visit to Beijing.

Andy Rothman

Investment Strategist

Matthews Asia

Source: CEIC