Our Thinking on Trump 2.0 Tariffs

Portfolio Manager Andrew Mattock, CFA, explains the importance of assessing U.S. tariffs as a component among external variables that can influence, rather than drive, investment returns.

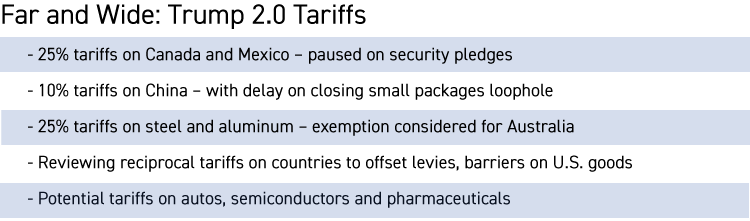

Watch VideoFive weeks into the new Trump presidency and one thing is clear: Trump 2.0 tariffs look very different to Trump 1.0 tariffs.

While Trump 1.0 duties were focused on goods being imported from a narrow range of countries, Trump 2.0 tariffs encompass nearly all regions and economies. They are also not focused on a fixed set of goods. The planned taxes on Canada and Mexico, for example, would apply to all exports into the U.S.

The other characteristic of Trump 2.0 tariffs is that they are a moving target. Many are subject to review and negotiation. The Trump administration’s proposed reciprocal tariffs on trading partners is potentially the most far-reaching of its tariff policies but it may also be the most complex to calculate and implement, in our view. And, as we have seen in the past, Trump tariffs are often used as bargaining tools in trade negotiations. A hard calculation of the economic and trade impact of Trump 2.0 tariffs would therefore seem to be a long way off.

“We don’t see production being shifted around too dramatically particularly as Trump 2.0 tariffs, as proposed, are being considered across lots of regions and markets.”

A better approach, we think, is to try to ascertain the rationale behind the U.S. tariff strategy. It helps us calibrate how and where the U.S. may commit to implement tariffs, negotiate trade deals, or provide tariff exemptions.

The Trump administration has been open about wanting to use tariffs as a revenue generating exercise and a tool with which to address trade deficits. Tariffs, along with cost cutting within Federal government departments, look to be a way of offsetting loss of income from potential future domestic tax cuts. In this context, its perhaps unsurprising that the tariff net is being cast far and wide across both developed and emerging market nations.

The Base Case

Given that U.S. tariff strategy is still evolving, it’s difficult to identify the geographical markets that could be the most affected. Will it be countries with high surpluses against the U.S., countries without trade deals, or countries with relatively high U.S. import barriers? Will it be economies in Europe or those in emerging markets?

One thing that does seem likely is that, based on current proposals to implement tariffs across many markets and regions, we don’t see production being dramatically shifted around the world. From a logistical standpoint, tariffs are something that can be imposed and withdrawn whereas moving production takes a lot of time and effort and is a more long-term process.

We also think that the U.S. is cognizant to the risk of tariffs contributing to another bout of inflation, so a tariff strategy could be approved if the administration believes price rises won’t be material to U.S. consumers, for example, in clothing or electronics; or it could be reined in if the administration believes it could trigger a surge in costs for consumers or businesses.

Individual Markets and Tariffs

North Asian markets supply components into an array of supply chains across the globe including semiconductors, electric vehicle (EV) batteries and autos. While Taiwan and South Korea are export-dependent, many of their products are essential and relatively high-value added. For example, companies from both countries provide memory and non-memory chips to final product manufacturers in China which then ship to end-markets in the U.S. or Europe. Short-term substitutes for these companies are hard to find at the similar level of cost competitiveness or manufacturing sophistication in certain cases. In addition, these companies have been seeking to mitigate geopolitical risk and trade duties with the U.S. by diversifying manufacturing bases closer to the end market.

India, along with Brazil, could be one of the most exposed economies to U.S. reciprocal tariffs, taking into account the import tariffs, taxes, currency and other barriers U.S. exports face. The Trump administration’s 25% tariff on steel imports could also hurt India as it is a large exporter to the U.S. However, as a strong ally with the U.S., India is also among the best positioned countries geopolitically to make a deal with Trump. Its economy is also mainly driven by its domestic growth agenda which is increasingly powered by manufacturing, industrials, financials and e-commerce.

For China, Trump signaled on the campaign trail that he was prepared to impose tariffs of as much as 60%. Currently there is a 10% duty and the U.S. administration has paused closing a loophole allowing the exemption of small packages. Trump has also signaled an openness to negotiate with China’s Xi Jinping. The U.S.-China tariff landscape could of course change very quickly. Right now, China is overly dependent on export revenue due to its faltering domestic economy so a ratcheting up of import duties would undoubtedly hurt the economy. We are also mindful of the possibility of a large retaliatory response from China to any aggressive new U.S. tariffs as well as potential domestic stimulus moves that they could trigger.

Japan is an ally of the U.S. but it is also a global trading and manufacturing hub and could be subject to tariffs on sectors. Japan could also be exposed to the U.S. reciprocal tariff program because of the duties it places on U.S. imports. However, in Japan’s favor is its trade deficit with the U.S., which is significantly smaller than those of other key U.S. trading nations including China, the EU and Mexico. Many Japanese companies have shifted production overseas including to the U.S. in recent years, so while the U.S. economy has grown, the trade deficit with Japan hasn’t notably widened. Japan’s average tariff rate is also similar to that of the U.S. so arguably U.S. tariffs are already reciprocal with Japan.

Like North Asia, the countries of the ASEAN region are highly exposed to global trade. For that reason, they could be impacted indirectly by tariffs on China, Mexico and Europe. Reciprocal tariffs could also have an impact as some ASEAN nations have large trade surpluses with the U.S. and levy imports duties on U.S. goods. In addition, markets including Vietnam have manufacturing hubs for Chinese companies which export to the U.S. and which could single them out for additional duties. On the flip side, some ASEAN countries, like the Philippines and Singapore, have allied relationships with the U.S. which may work to their favor.

For Mexico, the planned 25% tariffs on all exports to the U.S. could have a significant impact if fully implemented though that is by no means a given. The U.S. is the biggest exporter to Mexico and vice versa so it would seem that both countries would have a lot to lose from an escalating trade war. On the positive side, there is an existing trade deal between the U.S., Canada and Mexico that could be revised to accommodate new trade initiatives.

Our Approach

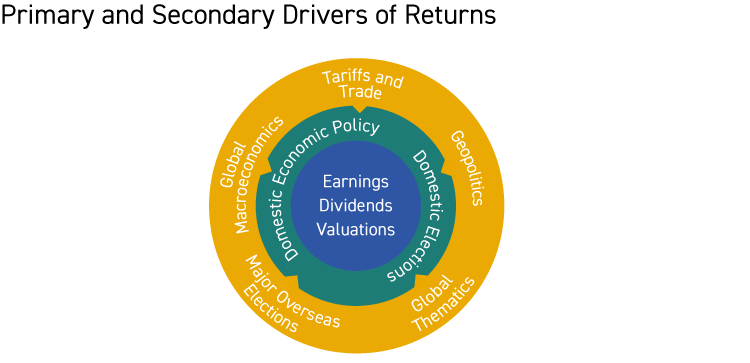

When we think about the impact of tariffs on investment returns, we think about them within the framework of our portfolio approach. We believe that earnings and domestic economic policy are among the key drivers and shapers of long-term investment returns.

In China's case, for example, we believe domestic economic policy aimed at revitalizing its property market is the key to its long-term economic recovery and in providing support for sustainable investment returns. For India, the country’s infrastructure reform process and continued growth in its urban economy and consumer markets we think will be fundamental to supporting equity returns. These two major emerging markets have stock markets that are skewed to domestic-orientated companies but even for other markets with more exposure to exports and world trade, we still place high emphasis on domestic economic policy. In our view, it determines the landscape upon which companies operate, in terms of taxation, regulation, government finances and macroeconomic policy.

In Conclusion

We believe tariffs are an important consideration, but they are an external variable to be accommodated into portfolio positioning along with other global factors like interest rates and investment themes like artificial intelligence (AI), as well as external developments like war and conflict. More significant for generating investor returns, in our view, are corporate earnings, dividends and valuations and the domestic economic policies of individual countries.

Many markets including China and India, in our opinion, still have huge growth potential to be realized from consumer penetration, agile and upskilling labor markets, urbanization and innovation. These structural assets of emerging markets, we believe, have the opportunity to make a much greater impact on long-term drivers of investment returns than overseas tariffs and trade policies.