Time for South Korea to Value Up

New moves to improve governance and unlock potential value in South Korea have significant long-term tailwinds but they will need the support of active investors, say Kathlyn Collins, Head of Responsible Investment and Stewardship, and Elli Lee, portfolio manager.

Key Takeaways

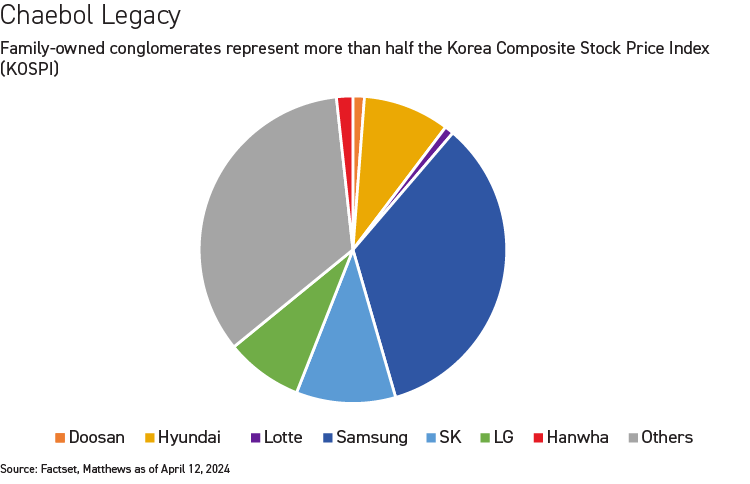

- South Korea’s dominant chaebol-structured conglomerates once helped to bring prosperity to the country; now they are hindering value creation for investors.

- The government’s ‘Value Up’ program seeks to encourage higher corporate standards and help unlock value but it faces resistance and needs more teeth.

- The good news is that Value Up has allies: younger people in South Korea are increasingly unwilling to inherit the chaebol structure and its obligations and retail investors want their voices to be heard.

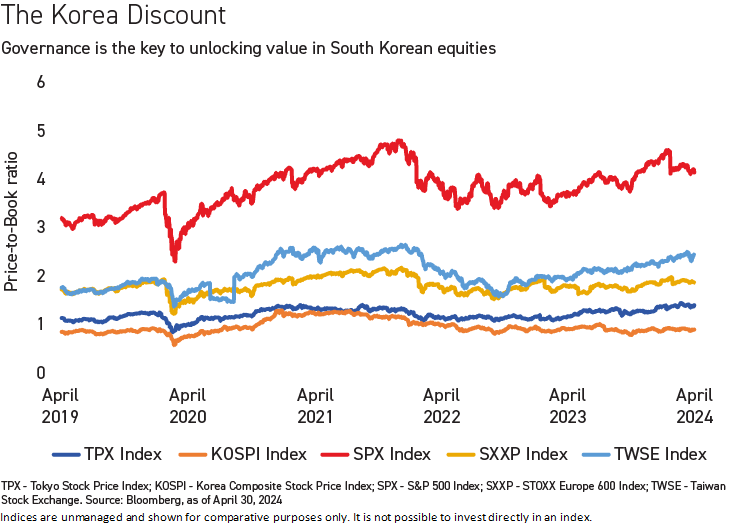

The increasing global focus on corporate governance is stirring shifts in the structure of markets and companies worldwide. These shifts are facing perhaps their biggest test in South Korea, a market known for its large, opaque, family-owned conglomerates which have powered the economy for decades while at the same time shutting off large parts of value creation from minority shareholders. Over the years, we’ve seen some improvement in the willingness of South Korean companies to engage with minority shareholders and make corporate governance changes but the basic infrastructure remains in place and has led to the entrenchment of what has become known as “the Korea discount.”

Kathlyn Collins, Head of Responsible Investment and Stewardship, and Elli Lee, portfolio manager, meeting regulators, investors and companies in Seoul in April.

South Korea's Corporate Value Up program, introduced by the Financial Services Commission (FSC) on February 26, is the latest initiative, and a promising effort in our view, to crack this tough nut and improve the corporate governance landscape and market practices in the country. The program's goals are far-reaching, aiming to align the interests of controlling and minority shareholders, enhance transparency and ultimately, unlock shareholder value. We got to see reception to the program first hand when we took part in the Asian Corporate Governance Association Korea Working Group’s meetings in Seoul during the annual general meeting (AGM) season earlier this year. Our investor group attended AGMs and engaged with companies, regulators, academics, asset owners and local think tanks.

“Value Up seeks changes in corporate law and regulations to foster a more transparent and fair business environment and puts forward initiatives to improve communication between companies and investors. It’s an ambitious brief.”

Kathlyn Collins, Head of Responsible Investment and Stewardship

We would say unequivocally that the program presents an excellent opportunity for companies and policymakers alike to have meaningful dialogues with stakeholders and shareholders. We are also encouraged that the Korea Exchange plans to display key financial indicators of companies on its website, categorized by market segments and business sectors. These indicators should include Price-to-Book Ratio (PBR), Price-to-Earnings Ratio (PER), Return on Equity (ROE), dividend payout and dividend yield. Additionally, the exchange will provide investor relations services to companies that lack the capability, particularly in English, to actively support them in enhancing their corporate value.

Enforcement Wanting

Having said all this, while the long-term prospects for Value Up are promising, its near-term impact is less clear. The program aims to encourage companies to voluntarily adopt higher governance standards, improve financial transparency and engage more constructively with shareholders. It also seeks changes in corporate law and regulations to foster a more transparent and fair business environment and puts forward initiatives to improve communication between companies and investors. It’s an ambitious brief.

And as soon as the measure came out of the blocks there was disappointment, centered mainly around the voluntary nature of the proposals. This month, as the program takes effect, the FSC followed up by offering more details on the reforms. However, in our meetings and conversations with the delegation it was apparent that most shareholders were hoping for stronger enforcement and for other reforms including stricter fiduciary responsibility for boards of directors and even a lowering of inheritance tax, which is seen by many as a key reason why South Korea’s large corporates are reluctant to improve capital efficiency and shareholder value.

“Many chaebols helped make South Korea an economic success but their scandals, conflicts of interest and often disregard for minority shareholders are now often cited as a reason behind the Korea discount.”

Kathlyn Collins, Head of Responsible Investment and Stewardship

One of the reasons for the Korea discount is said to be the weight of the South Korean family dynasties, or chaebols, on the market and their grip on the economy. These companies were established in the 1960s and helped make South Korea an economic success story. But their opaque structures, conflicts of interest, lack of regard for minority shareholders and some high profile scandals have marred their standing, and they are often cited as a key reason for the discount effect. The discount can be seen with these companies trading at lower earnings multiples versus global peers.

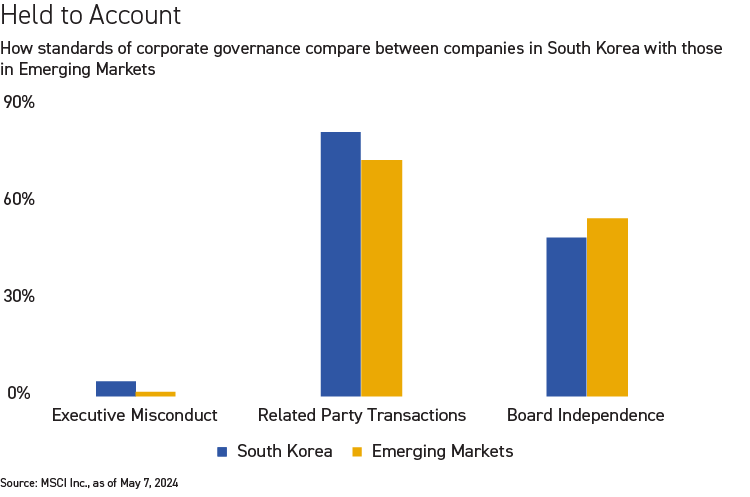

There have been attempts at the margin to improve the situation but they have largely become tools for chaebol owners to enlarge control. We have seen consultative fees increased, more related party transactions and more money coming from brand royalties than dividends. On top of that, these companies have different control-enhancing mechanisms which allow them voting rights which do not always align with the economic interest of the company.

Hoarding of capital by controlling shareholders has also contributed to the Korea discount. In general, dividends are low and overall shareholder returns are low despite South Korea’s stock market constituents having strong cash flow and balance sheets in many cases. Today, two thirds of South Korean companies trade below the book value of their assets, compared with less than half of Japanese companies.1 Consequently, we believe there is a lot of value to be unlocked if corporate governance reforms are followed through.

What has exacerbated the issue in our view has been economic policy misalignment. In the case of listed company owners, inheritance tax is effectively 60% and is an incentive for chaebols, with their complex intercorporate structures, to encourage low valuations of stock and reduce the impact of these taxes. Some observers believe that lowering the inheritance tax would motivate companies to increase shareholder value but there is also concern that such a move would be met with an adverse public response.

Chaebols and ‘Finfluencers’

So how best can we take the spirit and the mandate of the government’s Value Up program forward and what role can long-term active investors play? Clearly, stronger shareholder rights and improved access for minority shareholders is needed to promote better alignment with controlling shareholders to drive long term value, whether that is through tax reforms and shareholder return incentives, corporate law changes or regulatory reforms.

“When you have good corporate governance, it improves the value of companies as they try to make the best decisions for capital allocation that are linked directly to business decisions for improving long-term returns on capital.”

Elli Lee, Portfolio Manager

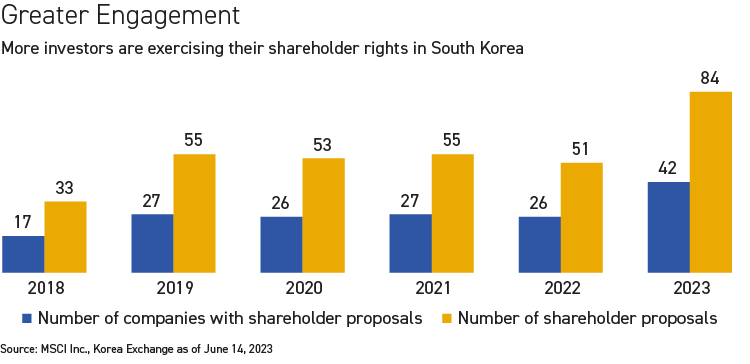

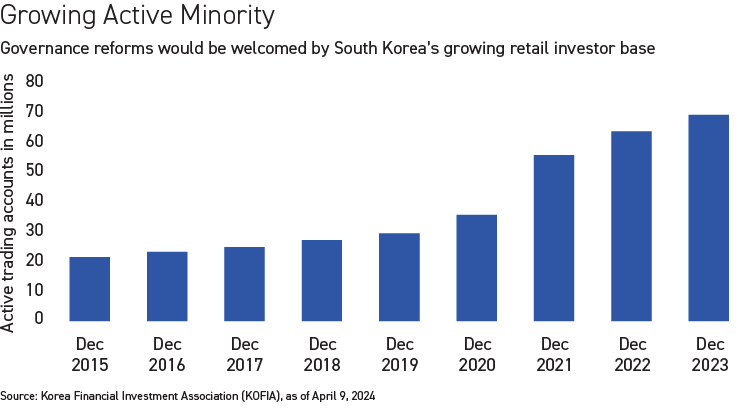

The good news is that the voice of retail shareholders is getting louder. One of the reasons behind the Value Up program is the political reality that retail shareholders now present and the fact that many of them have become frustrated with returns from domestic companies including chaebol conglomerates. Another positive is that reforms contemplated in Value Up are intertwined with other market reforms being pushed by regulators as a way of helping South Korea qualify for Developed Market status.

The media landscape has also greatly changed over the last few years as has the outlook of younger generation of South Koreans. Today, the chaebols’ influence over the media narrative has waned as younger investors get more of their news and information from ‘finfluencers’ and social media. Increasingly, South Korea’s younger generations also seem disinterested in being at the helm or involved in many of these large family-owned companies going forward. So the long term future and viability of the chaebol structure is in question, in our view.

The Role of Active Investors

We also believe there is an alignment on much of the concerns that retail shareholders have with the posture of long-term activist investors. We would argue that there is a key role that long-term investors can play especially if there are ongoing disappointments on the Value Up program. Foreign investors were quite optimistic when the initiative was launched but we will need to keep the momentum going. Disclosure should be improved, related party transactions should be monitored, mandatory takeover bids clarified, and stewardship should be encouraged. Long-term investors can engage and pressure companies to help realize these outcomes.

In addition, in our view, there are other issues that need to be prioritized in the program. Minority shareholders should be encouraged to exercise their rights to attend AGMs so that board directors and top management can hear our voices directly. Audit committee independence is an area that has improved accountability at large companies in South Korea and should also continue to be leveraged by shareholders.

Reduction or reform of inheritance tax might not necessarily make a big impact on corporate governance as large companies have tended to find ways to mitigate liability and the government is also heavily reliant on the tax for the health of the public finances. Alternatively, in our view, a reduction of dividend income tax and capital gains tax could lead to better alignment with minority shareholders if coupled with boosts in shareholder returns. Tax incentives for reduction of treasury shares or increased shareholder returns could also be options.

“The Value Up program is meaningful and important. It offers opportunities for government and shareholders to take an in-depth look at the reasons for discounted valuations and to come up with solutions. It’s like planting a seed.”

Elli Lee, Portfolio Manager

Compensation is another area that should be tackled in the Value Up program. Pay is weakly aligned with shareholders at South Korean corporates and remuneration disclosure is poor compared with other markets. For example, more than 60% of companies in the Korea Investable Markets Index (MSCI Korea IMI) lack a standing pay committee and have executives serving on their boards.2

Board accountability is also under review as a potential criteria for the program. One area where some stakeholders would like to see it improved is through an amendment to the Commercial Code. The proposal would be that not only should directors have fiduciary duty to the company but that fiduciary duty should also be to shareholders. Based on our meetings, this amendment is unlikely to happen. Even in the event that it did, such a change would also have to involve accompanying measures around enforcing shareholder rights.

Naming and Shaming

Finally, if the Value Up plan was messaged as something aimed at the greater good, with pensioners, for example, able to see aggregate yields improve, its chances of success may be higher. Some stakeholders have made this point directly to the National Pension Service with requests for it to increase its allocation to domestic equities and to stake a more active role to improve the corporate governance of the companies it invests in. For this to happen, Value Up has to have more teeth and investors need to see genuine reforms that incentivize corporates to make value enhancements. We think the FSC’s plan to create an index of companies that lists the valuations and capital efficiency indicators they have disclosed is a potentially powerful tool to separate those companies that are being responsive to shareholder needs and those that aren’t.

As we said earlier, South Korea has made progress in improving certain aspects of governance in recent years and active investors have recorded some significant wins. For example, the government clarified the large shareholding disclosure rule, or the so-called ‘5% rule’, in 2020 which was hugely important and key to getting a mass adoption of investors signing onto the Stewardship Code. Since 2019 there also has been a mandatory disclosure requirement of corporate governance reports for large companies. In 2022, we saw a diversity mandate for large company boards to have at least one female director. We are also encouraged that the Financial Supervisory Service (FSS) recently detailed regulations requiring listed companies to share details of shareholder proposals they receive and actions taken in response to proposals.

Many people like to compare South Korea’s program to that of Japan, perhaps to the ire of some stakeholders in South Korea. There is a sense of competition with Japan and that tinges conversations around comparisons made between the two programs and likelihood of success. Japan has put in place these measures over the last ten years and only recently are the efforts starting to bear fruit. South Korea has planted a seed and has just started on the journey. Despite some of Japan’s initiatives also being voluntary, it employed a name and shame approach and this has worked effectively and is something we believe that South Korea should consider taking on board.

We visited Seoul in April in the lead up to the parliamentary elections on April 10. The Democratic Party of Korea (DPK) and its allies secured a majority in the 300-seat unicameral parliament which was a blow to the People Power Party bloc and President Yoon Suk-yeol and a blow to corporate governance reforms. Structural changes are difficult without broad political consensus. During our visit, it was clear that the various agencies were not totally aligned on the best way forward with the program. Now that alignment is more challenged.

In summary, we believe South Korea’s Value Up program is to be welcomed. It holds significant promise for enhancing the value of South Korean companies and improving the investment climate in the market. It will be a slow process that is likely to move in fits and starts over the years and its success will depend on overcoming political and economic challenges, aligning the interests of various stakeholders, and implementing effective reforms. For active investors and responsible stewards of shareholder capital, Value Up presents both opportunities and risks, and will require careful analysis and monitoring of developments in South Korea’s market going forward.

Kathlyn Collins, CAIA

Vice President, Head of Responsible Investment and Stewardship

Matthews Asia

Elli Lee

Portfolio Manager

Matthews Asia

Good Value?

Our take on South Korea’s Value Up corporate governance program

Positives

- Enhanced shareholder rights: Value Up encourages more transparency on issues including stock split and stock listing plans and it promotes auditor independence. Its initiatives aim to better align shareholder interests and this could lead to unlocking of value for minority investors.

- Korea Exchange’s Value Up webpage (kind.krx.co.kr) will allow peer comparison for companies in the same industry or of the same size, with key metrics displayed such as PBR, PER, ROE, Return on Invested Capital (ROIC), Cost of Equity (COE), Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC), dividend payout and yield, and total shareholder return.

- Encourages CEOs/CFOs to participate in communication and boards to oversee managements’ development and implementation of Value Up plans.

- Improved investor confidence: By addressing governance issues and enhancing transparency, the program could boost investor confidence and attract more foreign investment.

- Market development: Reforms under the program could help South Korea advance toward achieving Developed Market status, making it more attractive to global investors.

Negatives

- Voluntary measures without penalty. According to exception clauses, if companies provide reasonable grounds for predictions and state a clear disclaimer, they may be exempted from penalties for lack of disclosure improvements.

- Lack of tax details to incentivize shareholder returns; only that tax changes will be announced in line with policy reforms.

- No proposed amendments to the Commercial Code to introduce fiduciary duty to all shareholders.

- Chaebol dominance: Significant influence of chaebol families over the economy poses challenges to reducing the Korea discount.

- Political Uncertainty: Lack of alignment among government agencies and the impact of opposing parties in institutions of power have created an unclear regulatory environment.

Note: Matthews’ portfolios held positions in the above securities with the exception of Hanwha Corp. as of May 9. 2024. The information on the securities mentioned above is presented solely for illustrative purposes and is not representative of the results of any particular security or product.

Definitions:

Cost of Equity (COE) is the return a company requires for an investment or the return an individual requires for an equity investment.

Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) is a company's average post-tax cost of capital from all sources, including stocks, bonds and other types of debt.

Korea Investable Markets Index (MSCI Korea IMI) measures the performance of large, mid and small cap segments of the South Korean market. The index covers about 99% of the Korean equity universe.

1As of April 29, 2024; 2As of May 8, 2024. Source: Factset